By Jenna Beam

Earlier this month, I decided to embark on my first backpacking trip in Congaree National Park in South Carolina (be warned: beautiful, but mosquito central). While walking through the forest, my fellow backpacker pointed out a massive vine of poison ivy… right where I was about to step! And that’s when I realized: I didn’t actually know what poison ivy looked like! As someone who hikes fairly often, this seemed like pretty critical knowledge that I was missing. Join me, while we learn what poison ivy looks like and why it makes us so itchy.

Image 1: A picture of a poison ivy vine with the characteristic “leaves of three.”

Poison ivy, or Toxicodendron radicans, is a flowering plant native to Asia and Eastern North America (there are other species native to Western regions). It’s a deciduous plant, meaning that its leaves fall off seasonally, usually during autumn, like trees. You can remember what poison ivy looks like by using the saying, “leaves of three, leave them be!” This refers to the way the leaves are arranged on the vine. As you can see in the picture below (image 1), the leaves are roughly shaped like almonds and come in groups of three.

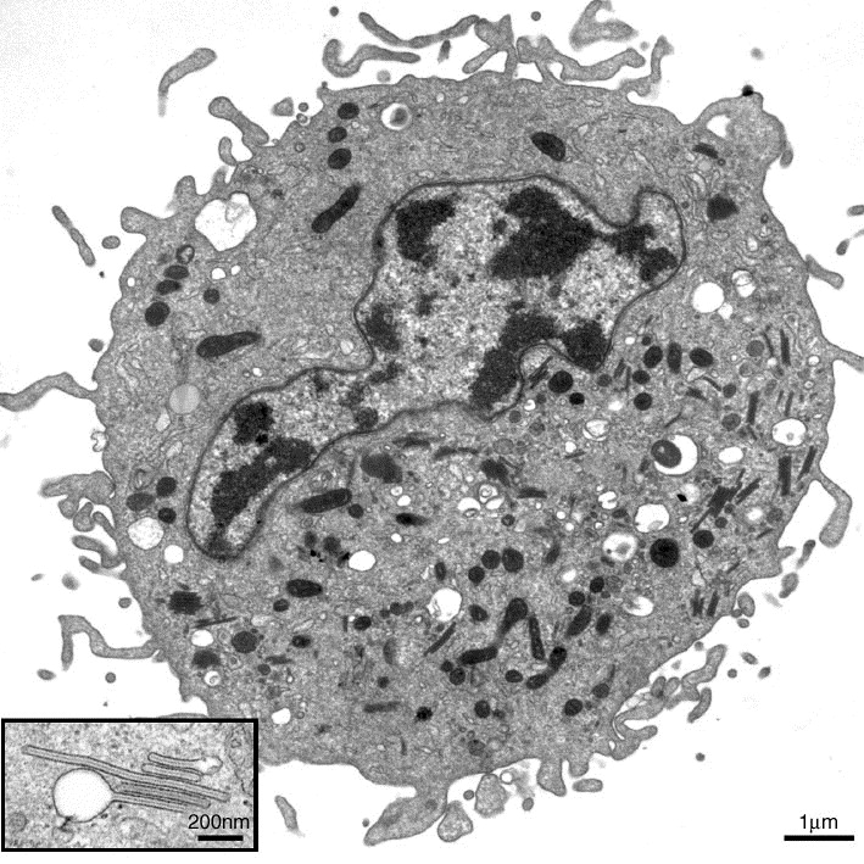

So now that we know what poison ivy looks like, let’s talk about why it makes you itch. Poison ivy causes what is called “urushiol-induced contact dermatitis,” or skin rash and blisters caused by coming into contact with the compound urushiol. Urushiol is an oil the plant produces that irritates the skin (fun fact: it’s the same oil in poison oak, poison sumac, and some mango trees!). When you brush against poison ivy, the oil absorbs into your skin where it reacts with proteins in your skin, forming what are sometimes called “urushiol-derivatives.” Once these derivatives form, they activate an immune response. This immune response is initially driven by special immune cells in the skin called Langerhans cells (image 2). After the Langerhans cells interact with the urushiol-derivatives, they travel to the lymph nodes, where they interact with another immune cell called a T-cell. The T-cells then travel back to the skin and produce chemicals called cytokines that ultimately damage the skin, resulting in a rash and blisters.

Image 2: A microscopy image of a Langerhans cell isolated from human skin.

Unfortunately for an unsuspecting hiker, the specific type of allergic reaction poison ivy and urushiol cause is called type VI hypersensitivity. This type of allergic reaction is a delayed allergic reaction, meaning that the rash and blisters won’t show up until a few days after the exposure. I’ll spare you all a photo of the rash, but if you’re feeling brave, click here.

Luckily, a poison ivy rash is treated pretty easily with a steroid cream, like hydrocortisone, or an anti-itch lotion. But maybe it’s better to just watch where you step.