By Mike Pablo

Today we have computers and technology all around us. While humanoid robotic helpers are still off in the future, I could define a robot as a machine that people can program or control to do useful tasks. In this sense, robots, already exist in useful forms, such as household appliances and cars. Arguably, those things aren’t what we picture as robots! Maybe we’re still missing something that’s a key part of ‘being a robot’.

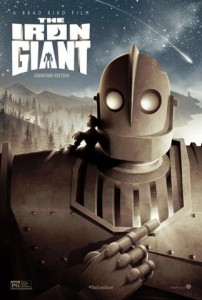

I bet you’d call this guy a robot, though. From the Iron Giant wiki.

Let’s think about the Iron Giant. It’s hard to argue that he’s not a robot: he’s a big, humanoid machine. He also doesn’t have to be constantly told what to do in order to function. So apart from the “looking human” aspect, I’ll add to the previous definition of a robot: A robot should be a machine that we can build and program to do useful things for us, but doesn’t need our constant supervision in order to do its job properly.

These kinds of robots exist too! Maybe that’s not surprising – I wouldn’t be writing this post if they didn’t – but it’s definitely exciting. We’re still in the early stages of robots becoming more useful for people. We’ve got the Roomba, an automatic vacuuming robot which has been around for a while, and self-driving cars, which are still in testing. However, it’s tricky to create robots that are good enough at their job that they don’t require supervision. It’s part of why Roombas are commercially available, but not self-driving cars: it’s not a big problem if a vacuum hits a wall, but it is a big deal if a car does.

What’s this got to do with science? In 1676, Isaac Newton wrote in a letter to Robert Hooke, “If I have seen further it is by standing on the shoulders of Giants”. Newton was using a metaphor which meant that we can understand more of the world around us than our ancestors could – but this is thanks to our ancestors’ work. This is a fundamental part of science. Without the work of Newton, Einstein, Curie, or countless other scientists who came before us, our understanding of the world would be far less complete. Computers became part of that story in the early-to-mid-20th century with great thanks to many people, including Margaret Hamilton, who was one of the pioneers in applying programming to solve difficult problems. Robots too have become part of the story, and today we owe some scientific progress to them.

Navigation software written by Margaret Hamilton and her team for the Apollo project to send people to the moon in the 1960s. From her Wikipedia Page.

Computers and computer science have continued to grow in sophistication. A major goal has been making robots capable of adapting to, or learning from, their environment. Researchers have designed machine learning algorithms, meant to help computers learn. These algorithms have helped robots figure out how to beat top-notch humans at complicated games, including Jeopardy and Go. And since the algorithms have succeeded in “teaching” robots to win complicated games, researchers are now trying to use them to teach robots to solve complicated real-world problems, from driving cars to suggesting optimal cancer treatments and designing new molecules.

Whether you call them robots or computers, these machines can do useful things without much supervision, making them tremendously useful. We can ask them to summarize humongous piles of data, to identify patterns we might not notice by eye, or even to prepare massive arrays of samples for testing. They almost seem like wizards that could replace us in the blink of an eye. But I think they’re closer to magic wands: after all, it’s still our job to ask the right questions, to collect the data, and to understand why the results might be important. With the help of new technological advances, I think we’ll be able to do more and see further than ever before.

Edited by Temperance Rowell and Tamara Vital